Corn

First grown in Mexico about 5,000 years ago, corn soon became the most important food crop in Central and North America. Throughout the region, Native Americans, Maya, Aztecs, and other Indians worshiped corn gods and developed a variety of myths about the origin, planting, growing, and harvesting of corn (also known as maize).

Corn Gods and Goddesses. The majority of corn deities are female and associated with fertility. They include the Cherokee goddess Selu; Yellow Woman and the Corn Mother goddess Iyatiku of the Keresan people of the American Southwest; and Chicomecoatl, the goddess of maize who was worshiped by the Aztecs of Mexico. The Maya believed that humans had been fashioned out of corn, and they based their calendar on the planting of the cornfield.

Male corn gods do appear in some legends. The Aztecs had a male counterpart to Chicomecoatl, called Centeotl, to whom they offered their blood each year, as well as some minor corn gods known as the Centzon Totochtin, or "the 400 rabbits." The Seminole figure Fas-ta-chee, a dwarf whose hair and body were made of corn, was another male corn god. He carried a bag of corn and taught the Seminoles how to grow, grind, and store corn for food. The Hurons of northeastern North America worshiped Iouskeha, who made corn, gave fire to the Hurons, and brought good weather.

The Zuni people of the southwestern United States have a myth about eight corn maidens. The young women are invisible, but their beautiful dancing movements can be seen when they dance with the growing corn as it waves in the wind. One day the young god Paiyatemu fell in love with the maidens, and they fled from him. While they were gone, a terrible famine spread across the land. Paiyatemu begged the maidens to turn back, and they returned to the Zuni and resumed their dance. As a result, the corn started to grow again.

Origins of Corn. A large number of Indian myths deal with the origin of corn and how it came to be grown by humans. Many of the tales center on a "Corn Mother" or other female figure who introduces corn to the people.

In one myth, told by the Creeks and other tribes of the southeastern United States, the Corn Woman is an old woman living with a family that does not know who she is. Every day she feeds the family corn dishes, but the members of the family cannot figure out where she gets the food.

One day, wanting to discover where the old woman gets the corn, the sons spy on her. Depending on the version of the story, the corn is either scabs or sores that she rubs off her body, washings from her feet, nail clippings, or even her feces. In all versions, the origin of the corn is disgusting, and once the family members know its origin, they refuse to eat it.

deity god or goddess

The Corn Woman solves the problem in one of several ways. In one version, she tells the sons to clear a large piece of ground, kill her, and drag her body around the clearing seven times. However, the sons clear only seven small spaces, cut off her head, and drag it around the seven spots. Wherever her blood fell, corn grew. According to the story, this is why corn only grows in some places and not all over the world.

In another account, the Corn Woman tells the boys to build a corn crib and lock her inside it for four days. At the end of that time, they open the crib and find it filled with corn. The Corn Woman then shows them how to use the corn.

Other stories of the origin of corn involve goddesses who choose men to teach the uses of corn and to spread the knowledge to their people. The Seneca Indians of the Northeast tell of a beautiful woman who lived on a cliff and sang to the village below. Her song told an old man to climb to the top and be her husband. At first, he refused because the climb was so steep, but the villagers persuaded him to go.

When the old man reached the top, the woman asked him to make love to her. She also taught him how to care for a young plant that would grow on the spot where they made love. The old man fainted as he embraced the woman, and when he awoke, the woman was gone. Five days later, he returned to the spot to find a corn plant. He husked the corn and gave some grains to each member of the tribe. The Seneca then shared their knowledge with other tribes, spreading corn around the world.

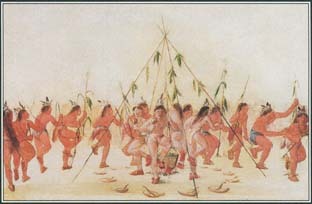

Green Corn Dance

Native Americans of the Southeast hold a Green Corn Dance to celebrate the New Year. This important ceremony, thanking the spirits for the harvest, takes place in July or August. None of the new corn can be eaten before the ceremony, which involves rituals of purification and forgiveness and a variety of dances. Finally, the new corn can be offered to a ceremonial fire, and a great feast follows.

Mayan stories give the ant—or some other small creature—credit for the discovery of corn. The ant hid the corn away in a hole in a mountain, but eventually the other animals found out about the corn and arranged for a bolt of lightning to split open the mountain so that they could have some corn too. The fox, coyote, parrot, and crow gave corn to the gods, who used it to create the first people. Although the gods' earlier attempts to create human beings out of

The Lakota Plains Indians say that a white she-buffalo brought their first corn. A beautiful woman appeared on the plain one day. When hunters approached her, she told them to prepare to welcome her. They built a lodge for the woman and waited for her to reappear. When she came, she gave four drops of her milk and told them to plant them, explaining that they would grow into corn. The woman then changed into a buffalo and disappeared.

Corn Mother. According to the Penobscot Indians, the Corn Mother was also the first mother of the people. Their creation myth says that after people began to fill the earth, they became so good at hunting that they killed most of the animals. The first mother of all the people cried because she had nothing to feed her children. When her husband asked what he could do, she told him to kill her and have her sons drag her body by its silky hair until her flesh was scraped from her bones. After burying her bones, they should return in seven months, when there would be food for the people. When the sons returned, they found corn plants with tassels like silken hair. Their mother's flesh had become the tender fruit of the corn.

Another Corn Mother goddess is Iyatiku, who appears in legends of the Keresan people, a Pueblo * group of the American Southwest. In the Keresan emergence story, Iyatiku leads human beings on a journey from underground up to the earth's surface. To provide food for them, she plants bits of her heart in fields to the north, west, south, and east. Later the pieces of Iyatiku's heart grow into fields of corn.

See also Aztec Mythology ; Mayan Mythology ; *=Native American Mythology .

* See Names and Places at the end of this volume for further information.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: