Aztec Mythology

The mythology of the Aztec civilization, which dominated central Mexico in the 1400s and early 1500s, described a universe of grandeur and dread. Worlds were created and destroyed in the myths, and splendid gods warred among themselves. Everyday items—colors, numbers, directions, days of the calendar—took on special meaning because each was associated with a deity. Aztec religious life ranged from keeping small pottery statues of the gods in homes to attending elaborate public ceremonies involving human sacrifice.

Origins and Influences

The Aztecs migrated to central Mexico from the north in the 1200s. According to their legends, they came from a land called Aztlan, the source of their name. The Aztecs were not a single people but several groups, including the Colhua-Mexica, the Mexica, and the Tenocha. In the early 1300s, these groups formed an alliance and together founded a city-state called Tenochtitlán on the site where Mexico City stands today. The people of Tenochtitlán rose to power and conquered a large empire during the 1400s.

The Aztecs were newcomers in a region long occupied by earlier civilizations such as those of the Olmecs and the Toltecs, who had developed a pantheon of gods and a body of myths and legends. The Aztecs absorbed deities, stories, and beliefs from these earlier peoples and from the Maya of southern Mexico. As a result, Aztec mythology contained religious and mythological traditions that many groups in Mexico and Central America shared. However, under the Aztecs certain aspects of the religion, notably human sacrifice, came to the forefront.

Major Themes and Deities

In the Aztec view of the universe, human life was small and insignificant. An individual's fate was shaped by forces beyond his or her control. The gods created people to work and fight for them. They did not offer favors or grant direct protection, although failure to serve the gods properly could lead to doom and destruction.

Main Themes. The idea that people were servants of the gods was a theme that ran through Aztec mythology. Humans had the responsibility of keeping the gods fed—otherwise, disaster could strike at any time. The food of the gods was a precious substance found in human blood. The need to satisfy the gods, especially the sun god, gave rise to a related theme: human sacrifice.

The Fiery Birth of the Sun

According to Aztec myth, at the beginning of this world, darkness covered the earth. The gods gathered at a sacred place and made a fire. Nanahuatzin, one of the gods, leaped into the fire and came out as the sun. However, before he could begin to move through the sky, the other gods had to give the sun their blood. This was one of several myths relating how the gods sacrificed themselves to set the world in motion. Through bloodletting and human sacrifice people imitated the sacrifices made by the gods—and kept the sun alive by feeding it with blood.

deity god or goddess

city-state independent state consisting of a city and its surrounding territory

pantheon all the gods of a particular culture

ritual ceremony that follows a set pattern

Priests conducted ceremonies at the temples, often with crowds in attendance. With song and dance, masked performers acted out myths, and the priests offered sacrifices. To prepare for the ceremonies, the priests performed a ritual called bloodletting, which involved pulling barbed cords across their tongues or other body parts to draw blood. Bloodletting was similar to a Mayan ceremony known as the Vision Quest. Peoples before the Aztecs had practiced human sacrifice, but the Aztecs made it the centerpiece of their rituals. Spanish explorers reported witnessing ceremonies in which hundreds of people met their deaths on sacrificial altars. The need for prisoners to sacrifice was one reason for the Aztecs's drive to conquer other Indians, although it was certainly not the only reason.

Sacrifice was linked to another theme, that of death and rebirth. The Aztecs believed that the world had died and been reborn several times and that the gods also died and were reborn. Sometimes the gods even sacrificed themselves for the good of the world. Though death loomed large in Aztec mythology, it was always balanced by fertility and the celebration of life and growth.

Another important idea in Aztec mythology was that a predetermined fate shaped human lives. The Aztec ball game, about which historians know little, may have been related to this theme. Aztec temples, like those of other peoples throughout Mexico and Central America, had walled courts where teams of players struck a rubber ball with their hips, elbows, and knees, trying to drive it through a stone ring. Some historians believe that the game represented the human struggle to control destiny. It was a religious ritual, not simply a sport, and players may have been sacrificed after the game.

The theme of fate was also reflected in the Aztecs' use of the calendar. Both the Aztecs and the Maya developed elaborate systems of recording dates with two calendars: a 365-day solar calendar, based on the position of the sun, and a 260-day ritual calendar used for divination. Each day of the ritual calendar was influenced by a unique combination of gods and goddesses. Divination involved interpreting the positive or negative meanings of these influences, which determined an individual's fate. Priests also used the ritual calendar to choose the most favorable days for such activities as erecting buildings, planting crops, and waging war.

The 365-day and 260-day cycles meshed, like a smaller wheel within a larger one, to create a 52-year cycle called the Calendar Round. At the end of a Calendar Round, the Aztecs put out all their fires. To begin a new Calendar Round, priests oversaw a ceremony in which new fires were lit from flames burning in a sacrificial victim's chest.

A third key theme of Aztec myth was that of duality, a balance between two equal and opposing forces. Many of the Aztec gods and goddesses were dualistic, which meant that they had two sides or roles. Deities often functioned in pairs or opposites. In addition, the same god could appear under multiple names or identities, perhaps because the Aztecs had blended elements of their myths from a variety of sources.

predetermined decided in advance

destiny future or fate of an individual or thing

divination act or practice of foretelling the future

primal earliest; existing before other

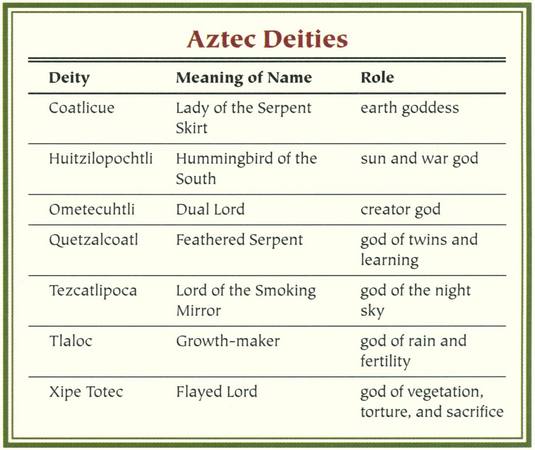

Major Deities. Duality was the basic element of the primal deity Ometecuhtli, who had a male side called Ometeotl and a female side known as Omecihuatl. The other gods and goddesses were their offspring. Their first four children were Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Huitzilopochtli, and Xipe Totec, the creator gods of Aztec mythology.

| Aztec Deities | ||

| Deity | Meaning of Name | Role |

| Coatlicue | Lady of the Serpent | earth goddess |

| Skirt | ||

| Huitzilopochtli | Hummingbird of the South | sun and war god |

| Ometecuhtli | Dual Lord | creator god |

| Qpetzalcoatl | Feathered Serpent | god of twins and learning |

| Tezcatlipoca | Lord of the Smoking Mirror | god of the night sky |

| Tlaloc | Growth-maker | god of rain and fertility |

| Xipe Totec | Flayed Lord | god of vegetation, torture, and sacrifice |

Originally a Toltec god, Tezcatlipoca (Lord of the Smoking Mirror) was god of the night sky. The color black and the direction north were associated with him. He possessed a magical mirror that allowed him to see inside people's hearts, and the Aztecs considered themselves his slaves. In his animal form, he appeared as a jaguar. His dual nature caused him to bring good fortune sometimes and misery at other times.

Tezcatlipoca's great rival and opponent in cosmic battles, as well as his partner in acts of creation, was Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent), an ancient Mexican and Central American deity associated in Aztec mythology with the color white and the direction west. Some stories about Quetzalcoatl refer to him as an earthly priest-king, suggesting that there may have been a Toltec king by that name whose legend became mixed with mythology.

As a god, Quetzalcoatl had many different aspects. He was the planet Venus (both a morning and an evening star), the god of twins, and the god of learning. The Aztecs credited him with inventing the calendar. A peaceful god, Quetzalcoatl accepted sacrifices of animals and jade but not of human blood. When he was defeated by Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl sailed out into the Atlantic Ocean on a raft of serpents. The legend arose that he would return over the sea from the east at the end of one of the Aztec 52-year calendar cycles. When the white-skinned Spanish invader Hernán Cortés landed in Mexico in 1519, some Aztecs thought he was Quetzalcoatl come again—a belief Cortés encouraged.

cosmic large or universal in scale; having to do with the universe

Huitzilopochtli (Hummingbird of the South), a deity that originated with the Aztecs, was the sun and war god. The souls of warriors who died in battle were said to become hummingbirds and follow him across the sky. Blue was his color and south his direction.

The Aztecs claimed that an idol of Huitzilopochtli had led them south during their long migration and told them to build their capital on the site where an eagle was seen eating a snake. The cult of Huitzilopochtli was especially strong in Tenochtitlán, which regarded him as the city's founding god.

Xipe Totec (Flayed Lord) had a dual nature as well. He was a god of vegetation, of life-giving spring growth, and at the same time, a fearsome god of torture and sacrifice. His double meaning reflected the Aztec vision of a universal balance in which new life had to be paid for in blood. Xipe Totec's color was red, his direction east.

The Aztecs took up in addition the worship of Tlaloc, an important god of rain and fertility long known under various names in Mexico and Central America. He governed a host of lesser gods called Tlaloques, who made thunder and rain by smashing their water jars. Other deities, such as Huitzilopochtli's mother, the earth goddess Coatlicue (Lady of the Serpent Skirt), probably played key parts in the religion of the common people, who were mainly farmers. Many deities were associated with flowers, summer, fertility, and corn.

Major Myths

Many Aztec myths tell all or part of the story of the five suns. The Aztecs believed that four suns, or worlds, had existed before theirs. In each case, catastrophic events had destroyed everything, and the world had come to an end.

Tezcatlipoca created the first sun, known as Nahui-Ocelotl, or Four-Jaguar. It came to an end when Quetzalcoatl struck down Tezcatlipoca, who became a jaguar and destroyed all the people. Quetzalcoatl was the ruler of the second sun, Nahui-Ehécatl, or Four-Wind. However, Tezcatlipoca threw Quetzalcoatl off his throne, and together the fallen god and the sun were carried off by a hurricane of wind. People turned into monkeys and fled into the forest.

The third sun, Nahuiquiahuitl or Four-Rain, belonged to the rain god Tlaloc. Quetzalcoatl destroyed it with fire that fell from the heavens. The water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue ruled the fourth sun, called Nahui-Atl or Four-Water. A 52-year flood destroyed that sun, and the people turned into fish.

The Loss of the Ancients

Many stories told of the Loss of the Ancients, the mythic event in which the first people disappeared from the earth. One version says that Tezcatlipoca stole the sun, but Quetzalcoatl chased him and knocked him back down to earth with a stick. Tezcatlipoca then changed into a jaguar and devoured the people who lived in that world. The Aztecs combined versions of this story to explain the disappearance of people at the end of each of the four worlds that had existed before theirs. Carvings on a stone calendar found in 1790 tell how jaguars, wind, fire, and flood in turn destroyed the Ancients.

cult group bound together by devotion to a particular person, belief, or god

The Aztecs lived in the world of Nahui-Ollin (Four-Movement), the fifth sun. They believed that the earth was a flat disk divided into north, east, south, and west quarters, each associated with a color, special gods, and certain days. At the center was Huehueteotl, god of fire. Above the earth were 13 heavens; below it were 9 underworlds, where the dead dwelled, making 9 an extremely unlucky number. A myth about Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl tells how the world was quartered. They made the earth by seizing a woman from the sky and pulling her into the shape of a cross. Her body became the earth, which, angered by their rough treatment, devoured the dead.

Another myth tells of Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl working together to raise the sky. After the flood that ended the fourth sun, the sky collapsed onto the earth. The two gods became trees, and as they grew, they pushed the sky up. Leaving the trees supporting the sky, one at each end of the earth, they climbed onto the sky and met in the Milky Way.

Quetzalcoatl gave life to the people of the fifth sun by gathering the bones of the only man and woman who had survived the long flood and sprinkling them with his own blood. The gods created the world with blood and required the sacrifice of human blood to keep it intact. One day, however, the fifth sun would meet its end in an all-destroying earthquake.

The Aztec Legacy

The Spanish destroyed as many Aztec documents and images as they could, believing the Aztec religion to be not just pagan but devilish. At the same time, however, much of what we know about Tenochtitlán and Aztec customs comes from accounts of Spanish writers who witnessed the last days of the Aztec empire.

pagan term used by early Christians to describe non-Christians and non-Christian beliefs

The legacy of Aztec mythology remains strong within Mexico. Aztec images and themes have influenced the arts and public life. In the late 1800s, Mexico had won independence from Spain but had not established its own national identity. Civic and cultural leaders of the new country began forming a vision of their past that was linked with the proud and powerful Aztec civilization. Symbols from Aztec carvings, such as images of the god Quetzalcoatl, began to appear on murals and postage stamps. Mexico's coat of arms featured an eagle clutching a snake in its beak, the mythic emblem of the founding of the Aztec capital.

During the 1920s, Mexico's education minister invited artists to paint murals on public buildings. The three foremost artists in this group were Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Although their works deal mainly with the Mexican Revolution and the hard life of Indians and peasants, the artists drew upon Aztec mythology for symbols and images to connect Mexico's present with its ancient past. Rivera, for example, once combined the images of the earth goddess Coatlicue and a piece of factory machinery. Aztec mythology has become part of Mexico's national identity.

See also Coatlicue ; Huehueteotl ; Huitzilopochtli ; Mayan Mythology ; Quetzalcoatl ; Sacrifice ; Tezcatlipoca ; Tlaloc .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: