Semitic Mythology

Semitic mythology arose among several cultures that flourished in the ancient Near East, a region that extended from Mesopotamia* in modern Iraq to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. These groups of people spoke Semitic languages, had similar religions, and worshiped related deities. Three great religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—grew out of Semitic traditions.

Semitic peoples shared many of the same myths and legends. Among their major gods and goddesses were those responsible for creation, fertility, death, and the afterlife. The names of the deities varied slightly from culture to culture. Common themes of Semitic myths included the creation of the world, a great flood, and a hero who overcame a challenge. Some themes, such as the death and rebirth of fertility gods, were rooted in the agricultural way of life of these Near Eastern peoples.

Origins. Between about 3000 and 300 B.C. , ancient Mesopotamia was home to a series of civilizations, beginning with the Sumerians, who built the first city-states. The Sumerians lived in the southern part of the region between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. They were followed by the Akkadians, who settled to the north, the Babylonians, and the Assyrians. Later, Sumer and Akkad became known as Babylonia. The Assyrians settled even farther north along the Tigris.

The Sumerians did not speak a Semitic language. However, the Akkadians and other Semitic peoples who later rose to power in Mesopotamia adopted many parts of Sumerian culture, mythology, and religion. This Sumerian influence shaped thinking and storytelling in the region for thousands of years.

deity god or goddess

city-state independent state consisting of a city and its surrounding territory

One of the central Sumerian myths, the story of Inanna and Dumuzi, shows how part of the ancient mythology survived in later cultures. Inanna, goddess of light, life, and fertility, was ready to choose a husband. Two men wanted to marry her—Enkimdu, a farmer, and Dumuzi, a shepherd. Inanna leaned toward Enkimdu, but Dumuzi told her that his flocks and herds of livestock could produce more wealth than could Enkimdu's fields. The rivals competed for Inanna's hand until Enkimdu withdrew. Enkimdu then allowed Dumuzi to graze his flocks on his land, and in turn Dumuzi invited Enkimdu to attend his wedding to the goddess. The rivalry between the farmer and the herder in this myth is echoed in the Jewish story of Cain and Abel. Some historians of mythology

| Semitic Deities | |

| Deity | Role |

| Adad, Ishkur, Addu, Hadad | Assyrian and Babylonian god of storms and weather |

| Allah | single, all-powerful God of Islam |

| Anat | Canaanite goddess of fertility, love, and war |

| Anu, An | chief creator and sky god |

| Ashur | main god of Assyria, warrior god |

| Baal | Canaanite god associated with rain and fertility |

| Dagon, Dagan | god associated with fertility, vegetation, and military strength |

| El, Elohim | Canaanite father of the gods, most high judge, creator god |

| Enki, Ea | creator god associated with water, storms, and wisdom |

| Enlil | god of creation, wind, land, and the sea |

| Ishtar, Inanna, Astarte | mother goddess of light, life, fertility, and love |

| Marduk | chief god of the Babylonians |

| Shamash | sun god |

| Yahweh | single, all-powerful God of Judaism |

believe that such tales grew out of ancient social tensions between settled agricultural communities and roving groups of livestock herders.

underworld land of the dead

Over time Inanna became known by her Akkadian name, Ishtar. Dumuzi also acquired other names—the people of early Israel called him Tammuz. One widespread story about Inanna and Dumuzi says that Inanna descended into the underworld and became a corpse there. The gods managed to restore her to life, but Dumuzi had to go to the underworld as her substitute. He came to be seen as a god of vegetation who had to die and be reborn each year. Many later myths about dying gods, including that of Adonis in Greek mythology, resemble the story of Inanna and Dumuzi.

Another basic Semitic myth that came from Sumer is the story of a flood that covered the earth after humans angered the gods. Warned by the gods (or God) to build a boat, one righteous man - such as Noah—and his family survived the flood to give humankind a new start.

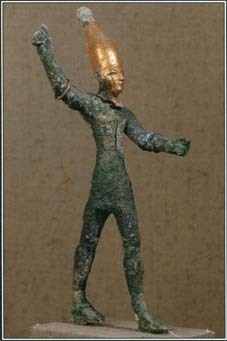

Mesopotamian Mythology. The myths of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians depicted a world full of mysterious spiritual powers that could threaten humans. People dreaded demons and ghosts and used magical spells for protection against them. They worshiped a pantheon of a dozen or so major deities and many other minor gods.

All Mesopotamian peoples honored a fertility goddess such as Inanna or Ishtar. They also recognized three creator gods, called An, Enlil, and Enki by the Sumerians and Anu, Enlil, and Ea by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. An was the chief of the gods. Enlil was a god of wind and land who could be destructive, and Enki was usually associated with water, wisdom, and the arts of civilization. The moon god, known as Sin or Nanna, appeared in a myth in which demons tried to devour him. The powerful god Marduk stopped the demons before they could finish the job. The moon god grew to his former size and repeated that growth every month, marking the passage of time.

The best-known Mesopotamian myth is the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh, the story of a hero king's search for immortality. A bold and brave warrior, Gilgamesh performed many extraordinary feats during his journey. Although he failed to obtain his goal—the secret of eternal life—he gained greater wisdom about how to make his life meaningful.

pantheon all the gods of a particular culture

epic long poem about legendary or historical heroes, written in a grand style

immortality ability to live forever

Another legend that deals with the question of why humans die is the myth of Adapa, the first human being. The water god Ea formed Adapa out of mud. Although Adapa was mortal, Ea's touch gave him divine strength and wisdom.

One day, when Adapa was fishing, the wind overturned his boat. Adapa cursed the wind. According to one version of the story, the wind was in the form of a bird, and Adapa tore off its wings. The high god Anu called Adapa to heaven to explain his actions. Adapa asked his father, Ea, for advice on how to act in heaven. Ea told him to wear mourning clothes, to be humble, and to refuse food and drink because they would kill him. So when Anu offered food, Adapa declined it. Unfortunately, Ea's advice had been mistaken. The food Adapa rejected was the food of immortality that would have allowed human beings to live forever. Adapa's choice meant that all men and women must die.

Mythology was closely interwoven with political power in ancient Mesopotamia. Monarchs were believed to rule by the will of the gods and were responsible for maintaining good relations between the heavenly world and their kingdoms. Each of the early city-states had as its patron one of the deities of the pantheon, and the importance of the god rose and fell with the fortunes of its city. A main theme of Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic, is the rise of Marduk, the patron god of Babylon. Marduk became a leader of the gods, just as Babylon rose to power in the region.

patron special guardian, protector, or supporter

Marduk appears again in a Babylonian myth about Zu, a bird god from the underworld. A frequent enemy of the other gods, Zu stole the tablets that gave Enlil control over the universe. When the high god Anu asked for a volunteer to attack Zu, several gods refused because of Zu's new power. Finally, Marduk took on Zu, defeated him, and recovered the tablets. This restored the universe to its proper order.

Canaanite Mythology. The Canaanites were Semitic peoples who occupied the lands along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Canaanite culture flourished in the city of Ugarit, on the Syrian coast, between 1500 and 1200 B.C. Their culture was continued by the Phoenicians, who settled south of Ugarit and later established a colony at Carthage in what is now Tunisia.

The chief of the Ugaritic pantheon was El, the father of the gods, who was generally portrayed as a wise old man. Baal, an active and powerful deity, was associated with fertility and sometimes identified with the storm god Adad. Ashera, the mother of the gods, was the wife of El.

The Invisible Queen

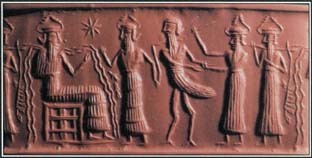

To the ancient Mesopotamians, light and darkness, life and death, were two halves of a whole. Inanna, the goddess of heaven, ruled the living world, and her sister Ereshkigal, or darkness, was queen of the dead. Neither sister could exist without the other—together they made existence complete. But while Inanna lived in the world that could be seen by humans, Ereshkigal was invisible. Mesopotamian artists never portrayed Ereshkigal directly, but they did create images of the monsters and demons that Ereshkigal sent to trouble the living.

Baal appears in a set of Ugaritic myths called the Baal cycle. These stories describe Baal's rise to power and the challenges he faced from other deities and powerful forces. An underlying theme of the Baal cycle is the tension between the old god El and the young and vigorous Baal. Although El remained supreme, Baal became a king among the gods. He defeated Yam, also called Leviathan, who represented the destructive force of nature and was associated with the sea or with floods. Baal also had to make peace with his sister Anat, a goddess of fertility, who conducted a bloody sacrifice of warriors. Finally, Baal and Anat went to the underworld to confront Mot, the god of death. El presided over the battle between Baal and Mot. Neither god won.

Other Ugaritic myths deal with legendary kings. Although these tales may have some basis in historical fact, the details are lost. One legend told the story of King Keret, who longed for a son. In a dream, El told Keret to take the princess of a neighboring kingdom as his wife. Promising to honor Anat and Ashera, the king did so, and his new wife bore seven sons and a daughter. However, Keret became ill and neglected the worship of the goddesses. Only a special ceremony to Baal could restore the king's health and the health of the kingdom. This myth illustrates the Semitic belief that the gods sent good or ill fortune to the people through the king.

Jewish Mythology. The ancient Israelites were a Semitic people who settled in Canaan. In time, they established the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, where the modern nation of Israel is today. In 722 B.C, the Assyrians gained control of the kingdom of Israel. The Babylonians conquered Judah in 586 B.C, destroying the city of Jerusalem and removing its inhabitants to Babylon for some years. Eventually the people of Judah came to be known as Jews.

Over the years the Jews produced sacred books, some of which form the Tanach, a set of documents known to Christians as the Old Testament of the Bible. These books include myths and legends about the history of the early Israelites as well as information about their religious beliefs. Traditional Jewish stories were influenced by ancient Semitic mythology. Connections are clearly seen in such stories as the fight between Cain and Abel and the great flood survived by Noah in his ark. In the same way, the story of creation in the book of Genesis in the Old Testament contains parallels to Mesopotamian myths about how Marduk organized the universe. One major difference between Jewish tradition and earlier Semitic mythology, however, is that Judaism was and is monotheistic. Instead of a pantheon of deities, it referred to a single, all-powerful God, sometimes called Yahweh.

As Judaism developed over the centuries, new stories, sacred books, and commentary emerged to expand on the ancient texts. The term midrash refers to this large body of Jewish sacred literature, including a vast number of myths, legends, fables, and stories that date from the medieval era or earlier. These narratives are called the Haggadah, or "telling," and they are cherished as both instruction and entertainment.

monotheistic believing in only one god

medieval relating to the Middle Ages in Europe, a period from about A.D. 500 to 1500

Sometimes the Haggadah fills in the gaps that exist in older narratives. For example, Genesis contains an account of how Cain

| Semitic Mythology | |||

| Other entries relating to Semitic mythology include | |||

| Adad | Balaam | Inanna | Nimrod |

| Adam and Eve | Cain and Abel | Ishtar | Noah |

| Anat | Dagon | Jezebel | Samson |

| Anu | Delilah | Job | Shamash |

| Ariel | Eden, Garden of | Jonah | Sheba, Queen of |

| Ark of the Covenant | El | Leviathan | Sheol |

| Armageddon | Enkidu | Lilith | Sodom and Gomorrah |

| Ashur | Enlil | Marduk | Telepinu |

| Baal | Enuma Elish | Moloch | Tiamat |

| Babel, Tower of | Gilgamesh | Nabu | Utnapishtim |

murdered Abel. The Haggadah adds the information that no one knew what to do with Abel's body, for his was the first death that humans had witnessed. Adam, the father of Cain and Abel, saw a raven dig a hole in the ground and bury a dead bird, and he decided to bury Abel in the same way.

Jewish tradition influenced Christianity, a monotheistic faith that began as an offshoot of Judaism. The two religions share many sacred stories and texts. The Tanach, especially the books of Genesis and Exodus, contains stories that are part of Christianity—God's creation of the earth, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Noah and the flood, and Moses and the Exodus. However, the New Testament of the Bible, which deals with the life and works of Jesus, is unique to Christianity.

Islamic Mythology. Like Christianity, Islam is a monotheistic Semitic faith that developed from Jewish traditions. Islam dates from A.D. 622, when an Arab named Muhammad declared himself to be the prophet of God, or Allah. Islamic tradition recognizes Abraham, Noah, Moses, and other ancient patriarchs of Judaism as earlier prophets. Muslims, followers of Islam, also believe that Jesus was a prophet.

The word of Allah as made known to Muhammad is contained in the Islamic sacred text, the Qur'an or Koran. As time passed, Muslim scholars and teachers all over the Islamic world added more information about Muhammad and his followers as well as interpretations of Islamic law and the sayings of the prophet. They incorporated elements of Semitic, Persian, and Greek mythology or stories about Muhammad, his family, and other key figures in Islamic history.

prophet one who claims to have received divine messages or insights

patriarch man who is the founder or oldest member of a group

Although such storytelling was not officially part of Islam—and was sometimes vigorously discouraged by Islamic authorities—it appealed to many Muslims. As Islam spread to new areas, local traditions and legends became mingled with the basic Islamic beliefs. In Pakistan, for example, old folk tales about girls dying of love came to be seen as symbols of souls longing to be united with Allah.

Many of the legends surrounding Muhammad credit him with miraculous events. Some tales say that Muhammad cast no shadow or that when he was about to eat poisoned meat, the food itself warned him not to taste it. According to legend, the angel Gabriel guided Muhammad, who rode a winged horse called Buraq or Borak, on a mystical journey through heaven, where he met the other prophets.

Similarly, historical figures who founded mystical Islamic brotherhoods came to be associated with stories of miracles, such as riding on lions and curing the sick. In some cases, these legends have elements of traditional myths about pre-Islamic deities or heroes. Romantic tales about Alexander the Great may have colored some of the tales about Khir, an Islamic mythical figure and the patron of travelers, who is said to have been a companion of Moses.

See also Devils and Demons ; Floods ; Persian Mythology ; Satan ; Scapegoat .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: