Heroes

At the heart of many of the world's most enduring myths and legends is a hero, a man or woman who triumphs over obstacles. Heroes are not all-powerful and immortal beings. Instead they represent the best of what it means to be human, demonstrating great strength, courage, wisdom, cleverness, or devotion.

immortal able to live forever

Not all heroes possess all these qualities. Through the ages cultures have produced various kinds of heroes who represent a wide

* See Names and Places at the end of this volume for further information.

range of virtues. The male-dominated civilization of ancient Greece, for example, admired strong warrior heroes. By contrast, in the mythology of ancient Egypt, where religion played a central role at all levels of society, the heroes were often priest-magicians. In many cultures women became heroes by using their intelligence or forceful personalities to outwit a foe.

Some heroes of myth and legend are wholly fictional. Others are historical figures who have risen to the level of legendary heroes or who have been given such status by writers or by the public.

The Universal Myth

In studying myths and legends from around the world, scholars have identified a pattern that appears over and over again—the story of the universal hero. The writer Joseph Campbell has shown that these stories generally end with the hero gaining new knowledge or abilities. Often an element of miracle or mystery surrounds the birth of such heroes. Their true identity may be unknown; they may be the child of a virgin; or they may possess special powers or be demigods.

Many hero myths focus on a quest—a difficult task or journey that must be undertaken to achieve a goal or earn a reward such as the hand of a loved one. Leaving the everyday world, the hero follows a path filled with challenges and adventures, perhaps involving magic or the supernatural. A hero may even enter the underworld and confront death itself.

Heroes must use strength, wits, or both to defeat enemies, monsters, or demons, although some are aided by luck or by a protective deity or magician. Sometimes heroes have to give up something precious to move forward in the quest. In the end the hero returns home enriched with powers, wisdom, treasure, or perhaps a mate won in the course of the quest.

The hero's quest may be seen as a symbol of the journey of self-discovery that anyone can make, the quest to overcome inner monsters and achieve self-understanding. But though quests form the basis of many myths and legends, not all heroes follow the quest pattern entirely or even in part.

Kinds of Heroes

There are almost as many kinds of heroes as there are human qualities and experiences. A great number of them fall into two or more categories.

demigod one who is part human and part god

supernatural related to forces beyond the normal world; magical or miraculous

underworld land of the dead

deity god or goddess

epic long poem about legendary or historical heroes, written in a grand style

Questing or Journeying Heroes. The hero on a quest or journey appears in dozens of myths, epics, legends, and fairy tales. Greek mythology has many questing heroes, including Odysseus*, Orpheus*, Jason*, and Hercules*. Odysseus just wants to return home after the Trojan War, but his adventure-filled voyage takes ten years. The musician Orpheus descends into the underworld in his quest to bring his beloved Eurydice back from death. Jason sails to distant lands in search of the Golden Fleece. The trials of the mighty Hercules are organized into Twelve Labors or quests.

Questing heroes appear in the mythology of many other cultures. Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic from ancient Mesopotamia*, travels in search of immortality. The Polynesian hero Rupe changes into a bird to search for his lost sister and bring her home. In Britain's Arthurian legends the knight Lancelot and his son Galahad seek the Holy Grail, and in a myth of the Tewa of North America, Water Jar Boy searches for his father—a symbol of the search for identity.

Warriors and Kings. A number of individuals rise to the level of heroes with their outstanding skills in combat. In myths about the Trojan War*, the warriors Ajax* and Achilles* fight valiantly and the Amazon* queen Penthesilea leads a troop of her soldiers against the Greek forces. Beowulf is the monster-slaying hero of an early English epic. Chinese myths tell of Yi, an archer so skilled that he was able to shoot down extra suns in the sky. Rama, hero of the Hindu epic the Ramayana, defeats fearsome demons called Rakshasas in a series of duels. The Celtici hero Finn leads a band of warriors against animal, human, and supernatural foes. Various Native American legends feature pairs of warriors—such as the Navajo warrior twins and the Zuni Ahayuuta brothers—who perform heroic tasks to help their people.

Some figures in mythology earned their hero status as legendary rulers. Britain's King Arthur, for example, may have begun as a historical figure but was transformed into a hero of great stature. Africa has a strong tradition of kingly heroes. Shaka, a leader of the Zulu people of southern Africa, gathered a huge army and established a great empire in the early 1800s. Osai Tutu, a ruler of the Ashanti people in the 1700s, succeeded in freeing the Ashanti from domination by a neighboring people with the help of a magical golden stool. Tibetans and Mongolians tell tales about the warrior-king Gesar (Gesar Khan), a god who reluctantly agreed to be born as a human in order to fight demons on earth.

Holy grail sacred cup said to have been used by Jesus Christ as the Last Supper

National and Culture Heroes. A national hero is a mythological—or even historical—hero who is considered to be the founder of a city or nation or the source of identity for a people. In ancient Greece, heroes became the object of

* See Names and Places at the end of this volume for further information.

religious worship, and local cults developed to show devotion to particular local heroes. The Romans made Aeneas* their national hero. In North America, Iroquois legends say that the hero Hiawatha persuaded five tribes to come together as one group, thus giving the Iroquois greater power and a stronger identity.

Another type of ancestral hero is the culture hero who brings the gifts of civilization to a people. The Kayapo Indians of Brazil have a myth about a boy named Botoque, who stole fire from a jaguar and brought it to his people so they could cook food for the first time. In Greek mythology it is the Titan* Prometheus who steals fire for the benefit of humankind. The Daribi people of Papua New Guinea, a large island in the eastern Pacific, have myths about Souw, a wandering culture hero. Souw brought death, warfare, and black magic, but he also gave humans the first livestock and crops, allowing them to shift from hunting to agriculture.

Clever Heroes and Tricksters. In many myths heroes accomplish great tasks by outwitting evil or more powerful enemies. In the West African legend of Sunjata, the female character Nana Triban tricks the evil king Sumanguru Kante into telling her the source of his great strength. Nana Triban uses this knowledge to help her brother Sunjata triumph over Sumanguru. In Greek mythology, Penelope, the wife of Odysseus, outwits the many suitors pressing to marry her during her husband's long absence. Claiming that she must weave a shroud for her father-in-law before she can remarry, she weaves by day and unravels the cloth by night. In the Persian tale Thousand and One Nights, Sheherazade prevents the sultan from carrying out a plan to kill her. Capturing his attention with fascinating stories, she withholds the endings, promising to continue the following evening.

Some culture heroes are tricksters—human or animal characters whose mischievous pranks and tricks can benefit humans. Raven and Coyote fill the trickster role in many Native American myths. The Polynesians of the Pacific islands have myths about Maui, a trickster whose actions have bad results as often as good ones. He loses immortality for humans, for example, but acquires fire for them. Tricksters in African myth are generally small and weak creatures, such as the hare and the spider, who outwit the strong, rich, and powerful. The African trickster hare is the distant ancestor of Brer Rabbit, a clever hero in African American mythology.

Folk Heroes. Some heroes are ordinary individuals who have special skills. They may take up the causes of common people against tyrants and bullies or may be blessed with remarkable good fortune. Such heroes often become known through popular songs or folk tales, but they may also appear in various forms of literature.

Born Under a Hero's Star

Unusual circumstances often mark the birth of a mythic hero. The hero may be the result of a mixed union—Hercules was the son of the god Zeus* and of a mortal woman. Some heroes do not even need two parents. Kutoyis, a hero of the Native American Blackfoot people, was born as a clot of blood dropped by a buffalo. Kama, a hero of the Hindu Mahabharata, is born to a woman who is a virgin—a theme that occurs in many myths. The African Bantu people tell of Litulone, the child of an old woman who produced him without a man's help. Like Hercules, the Irish hero Cuchulain, and many others, Litulone had great strength and fighting skill when barely out of infancy.

cult group bound together by devotion to a particular person, belief, or god

Folk heroes include Robin Hood, an English adventurer who fought and robbed the rich in order to help the poor, and John Henry, an African American laborer who performed a humble job with exceptional—and fatal—strength and determination. With its democratic traditions that recognize the worth of ordinary people, the United States has produced a number of folk heroes, including Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Wyatt Earp.

Defiant and Doomed Heroes. The hero's story does not always have a happy ending. Some heroes knowingly defy the limits placed on them by society or the gods. Even if they face destruction, they are determined to be true to their beliefs—or perhaps to perish in a blaze of glory. Others are simply the victims of their own failings or of bad luck.

medieval relating to the Middle Ages in Europe, a period from about A . D . 500 to 1500

Yamato-takeru, a legendary warrior hero of Japan, brings about his own end when he kills two gods who have taken the form of a white deer and a white boar. Roland, a warrior hero of medieval European legends, falls in battle because he is too proud to summon help. Antigone, a Greek princess, defies the law in order to bury her brother, knowing that the penalty will be death. The most gruesomely doomed of all heroes may be Antigone's father, Oedipus, who outrages the gods by unwittingly killing his father

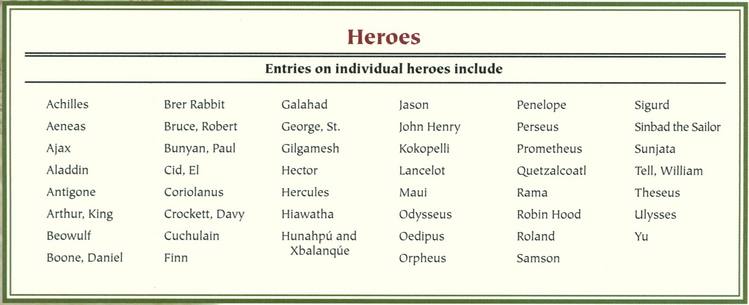

| Heroes | |||||

| Entries on individual heroes include | |||||

| Achilles | Brer Rabbit | Galahad | Jason | Penelope | Sigurd |

| Aeneas | Bruce, Robert | George, St. | John Henry | Perseus | Sinbad the Sailor |

| Ajax | Bunyan, Paul | Gilgamesh | Kokopelli | Prometheus | Sunjata |

| Aladdin | Cid, El | Hector | Lancelot | Quetzalcoatl | Tell, William |

| Antigone | Coriolanus | Hercules | Maui | Rama | Theseus |

| Arthur, King | Crockett, Davy | Hiawatha | Odysseus | Robin Hood | Ulysses |

| Beowulf | Cuchulain | Hunahpú and | Oedipus | Roland | Yu |

| Boone, Daniel | Finn | Xbalanqúe | Orpheus | Samson | |

and marrying his mother. His heroism lies not in quests, adventures, or triumphs but in facing his tragic fate.

In Aztec myths, the culture hero Quetzalcoatl was tricked by his enemy Tezcatlipoca into leaving his kingdom. After getting Quetzalcoatl drunk, Tezcatlipoca showed him a mirror with Tezcatlipoca's frightening image. Believing that the mirror reflected his own face, Quetzalcoatl went away to purify himself, promising to return to his people at the end of a 52-year cycle.

See also Tricksters .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: